Last Sunday afternoon (May 18, ’14), I took a group of alumnae of Finch College – in town for a college reunion – on a walk of Art Deco architecture on the Upper East Side. After visits to Raymond Hood’s 1928 apartment house at 3 East 84th Street, Harry Allen Jacob’s 1930 town house at 49 East 80th Street, and the 1930 Carlyle Hotel on Madison Avenue, we stopped in front of the former Finch College Museum of Art building (completely refaced for a new owner) at 62-64 East 78th Street. Though Finch College closed in 1976, its alumnae remain committed to their memories of the small women’s arts college, and reminisced about their time there decades ago. Several of the alumnae remembered the ground-breaking Art Deco exhibits at the Finch College Museum of Art – and also remembered its director, Elayne Varian (d. 1987), who organized the shows. They recalled her as “avant-garde” and a major force at the College.

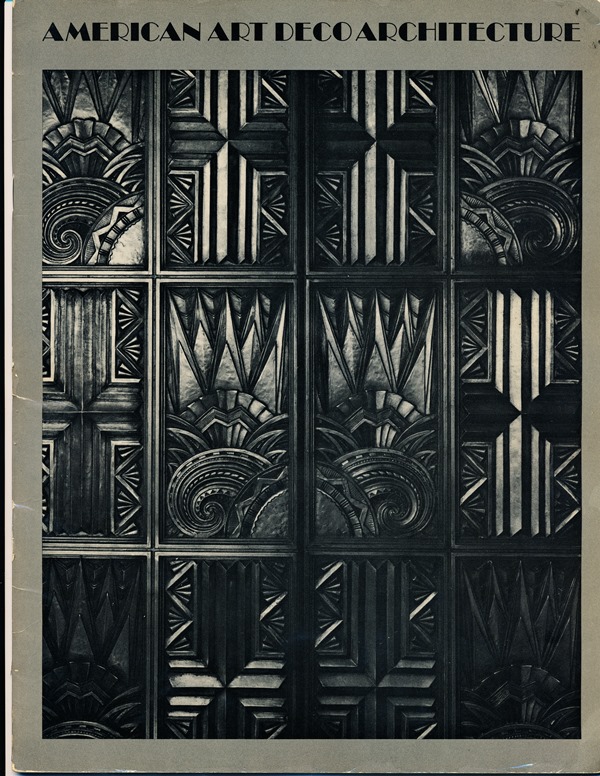

I brought along my prized copies of the two Finch College Art Deco exhibition catalogs – one from 1970 devoted to objects, and one from 1974-75 looking at architecture. These were the first important New York shows devoted to the subject – and got a lot of press coverage at the time.

The 1970 show – which then traveled to the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan – included “painting and sculpture,” “drawings, illustrations and posters,” “book bindings,” “books,” “jewelry,” “furniture,” “lamps,” “ceramics, glass and enamel,” “silver,” “objects,” and “costume jewelry and accessories” – 558 objects in all, more than 100 of them illustrated in the 48-page-long catalog (“Distributed by Wittenborn Art Books” – a long defunct Madison Avenue bookstore that art lovers and scholars of a certain age remember with reverence).

Professor Varian, who organized the show, wrote an introduction to the catalog:

“The great international style moderne involving all the creative artists of the period was a compilation of two radical factors, austere purity, involving new concepts of architectural space inspiring the use of current industrial materials of glass, cement, steel and bakelite, and the French decorative quality challenging its own tradition in favor of refinements of simplicity. Art Deco flourished during the torment of World War I and the Russian Revolution and became the school of art between the wars…. The beauty of perfect unity between form and function is shown in the execution of its objects.”

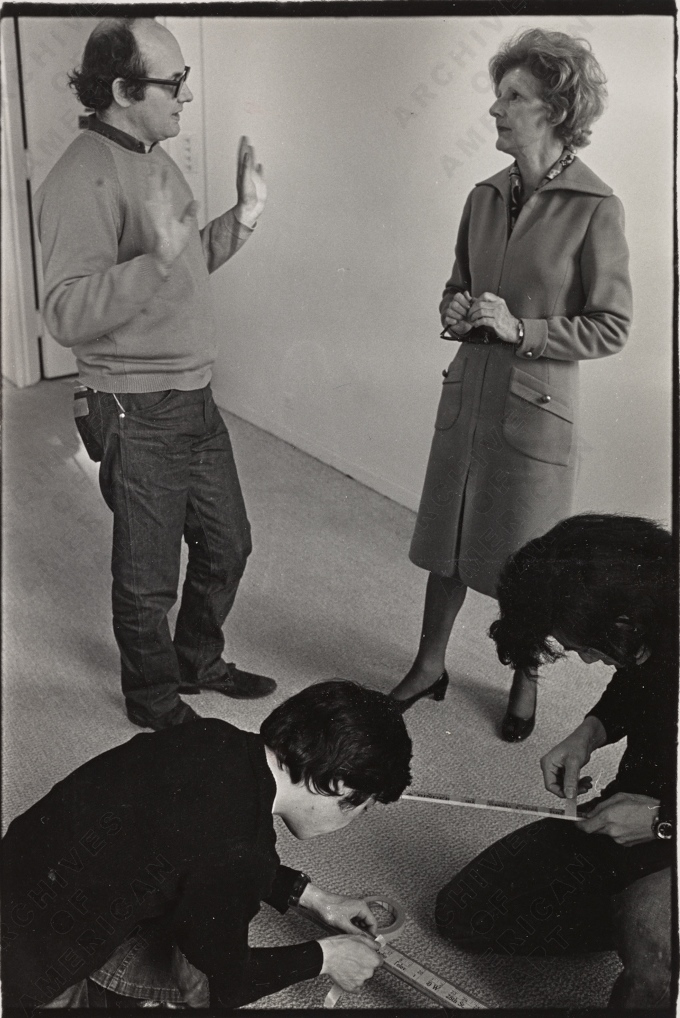

(Elayne Varian in 1972 with Sol Le Wit – nothing to do with Art Deco – at the Finch College Museum of Art; from the Archives of American Art)

Professor Varian went on to recount her pleasure in collaborating with Cranbrook, and then described her meeting with Bevis Hillier, who had written his own book called “Art Deco” in 1968, just two years after the French show of 1966 that named the style:

“Mr. Bevis Hillier, previously associated with the British Museum and now an arts correspondent for The Times in London was invited by The Minneapolis Institute of Arts to be the guest curator for the Art Deco exhibition in 1971. We met on his first trip to the United States, discussed our mutual interest in the art of the 1920’s and 1930’s and found we had selected the same objects from several collections. Mr. David Ryan, Curator of Exhibitions at the Minneapolis Institute of Art joined us and we continued to work together with enthusiasm and harmony. The Art Deco exhibition at The Finch College Museum of Art, which is scheduled to travel to the Museum of Cranbrook Academy early in 1971, will then continue on to The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, there to be expanded.”

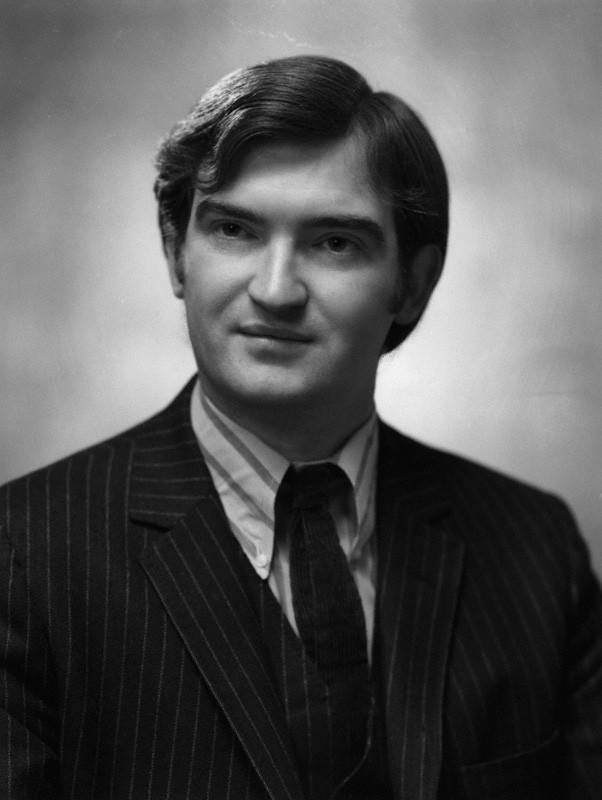

[Bevis Hillier – shown here in a 1968 portrait from the National Portrait Gallery in London – besides being an “arts correspondent” for The Times, was also editor of The Connoisseur – a long-since defunct arts magazine. In 1974, while I was a graduate student in London, he commissioned an article from me on the painter Antonello da Messina, for an all-Sicily issue, and took me to lunch to discuss the assignment. At the time, I’d never heard of Finch College or Art Deco. But lunch in the early 1970s to discuss an arts project with Bevis Hillier is something I can now say I share with Elayne Varian.]

Prof. Varian closed her introduction with a “thank you” to dozens of people, some of whose names will jump out at us today: “We enjoyed the encouragement of Andy Warhol….” and “are grateful to the following private collectors: … Mr. and Mrs. Leo Castelli… Mr. and Mrs. Don Judd… Mr. and Mrs. Warner LeRoy, Mr. and Mrs. Roy Lichtenstein… Miss Barbra Streisand….” And a little throw-away line: “we thank…John Vassos for his recollections of the ‘roaring twenties.'” John Vassos, a free-lance industrial designer, brought the “streamlined” look to RCA radio cabinets, Coca-cola soda dispensers, and an early 1930s version of the New York City subway turnstile.

Besides the introduction, the catalog included a piece by Judith Applegate, who, according to Prof. Varian, “has been researching this subject for two years on a Fulbright Grant for her doctorate from the University of Chicago, her thesis being entitled La Compagnie des Arts Francais de Louis Süe and André Mare, 1919-1927: Decorative Arts in France after World War One. Miss Applegate is the Paris Editor of Art International.”

Miss Applegate closed her write-up with a wonderful paragraph:

“The 1925 Exposition both summed up and apotheosized the Art Deco style… basically a heady mixture of Sheherezade exoticism, newly discovered East European folk art, stylization and simplification of old Art Nouveau motifs, classical geometrical formulae, Cubism, the machine… all somehow mysteriously combined with nationalism and a post-war back to normal optimism. Despite its diversity, Art Deco may be regarded as a fever-chart of the fairly consistent preoccupations of an age assaulted by both political power struggles and advancing technologies that promised great improvements for all…. But most important, Art Deco, in its restless search for a direction and an identity is a graphic manifestation of society’s realization of the overwhelming changes that, with ever increasing acceleration, typify the twentieth century.”

In 1974-75, the Museum turned its attention to Art Deco architecture. Prof. Varian wrote all the text this time, as well as selecting all the items – 54 in all. Building locations included Aberdeen (SD), Bloomfield Hills (MI), Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit, Lincoln (NEB), Kalamazoo (MI), Kansas City (MO), Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Oakland, Portland (OR), Philadelphia, Phoenix, Providence, Royal Oak (MI), St. Paul (MINN), Shreveport (LA), Syracuse (NY), Tulsa, and Washington (DC) – plus the Hoover Dam – but by far the greatest number were in New York City. Included: Bonwit Teller, the Chanin Building, the Chrysler Building (by far the most photos in the catalog), the Daily News Building, the Edison Hotel, the General Electric Building, the Knights of Pythias Hall, the S.H. Kress and Company Store, the McGraw-Hill Building, Rockefeller Center, Sixty Wall Tower (now 70 Pine Street), the St. George Hotel (Brooklyn Heights), the Waldorf-Astoria, and the Western Union Building. Besides overviews of buildings, the catalog included photos of sculpture and murals, early drawings of the Chrysler Building, doors, elevator cabs, elevator doors, elevator control panels, radiator grilles, terrazzo floors, and mail boxes.

Prof. Varian’s text is too lengthy to include here, but she does make one interesting plea:

“There are over 150 Art Deco buildings in New York City [well, there are a great many more than that, but never mind] and we hope the New York Landmarks Commission will designate the most important structures before a tragedy occurs….” Happily, in the intervening decades almost every New York building in the exhibit has been designated an official landmark. For a list of those, with links to their official designation reports (lengthy research papers), click here.

0 Comments